This is the second in a series of posts exploring three swords in Beowulf that are described with the phrase ealdsweord eotonisc – “old, trollish sword”. Part I can be found here.

In this post, we find the second eotonisc sword in Beowulf. Like the first, this one emerges during the action of a fight against a monster – here, the dragon. All three eotonisc swords enter the poem in this way: they are not introduced before battle is joined, but appear suddenly after the fight is already well begun and is seeming to turn against the victor. In all cases, these swords themselves are essential to resolving the climactic action of the encounter.

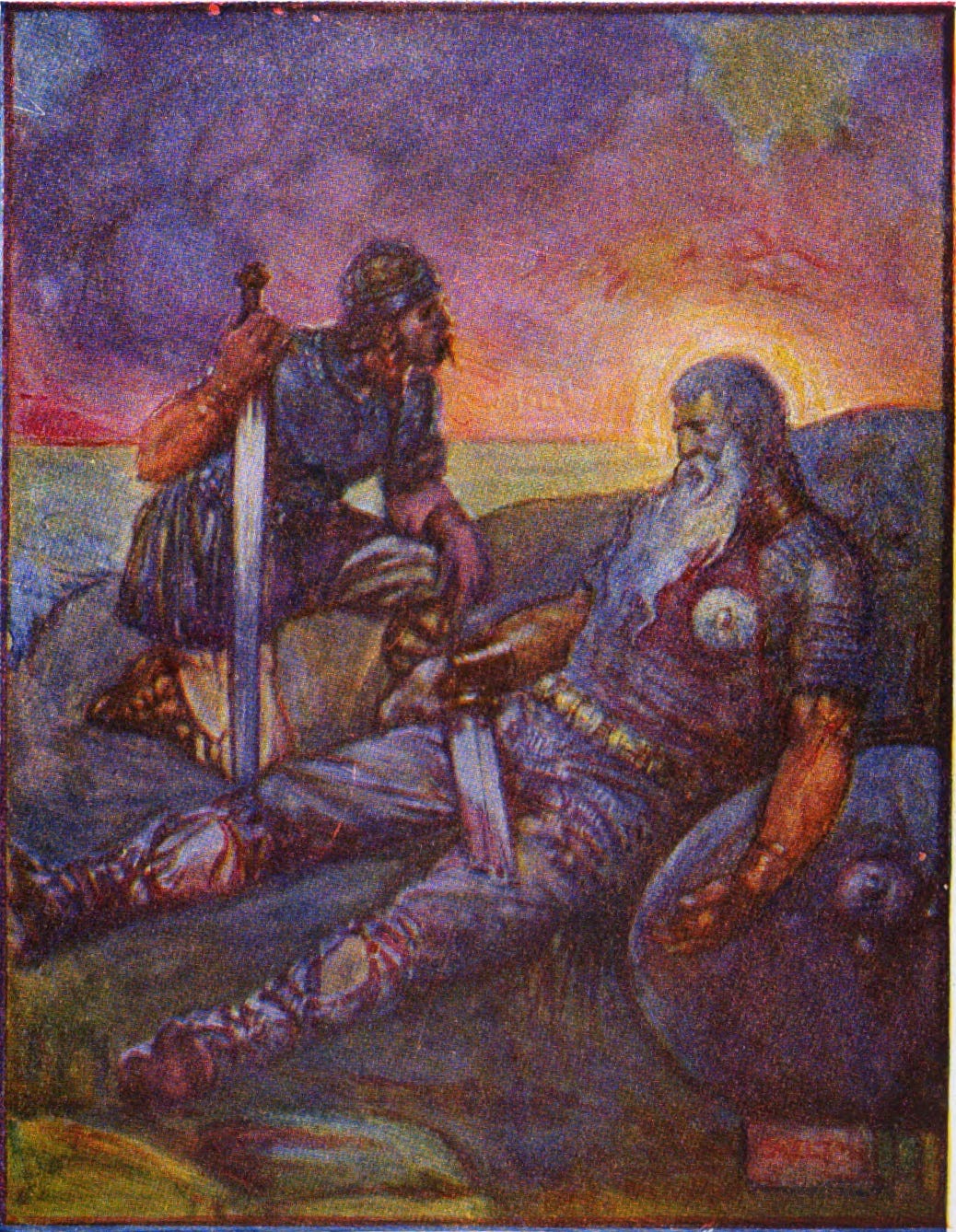

The dragon is an opponent Beowulf faces in his old age. He has been king of the Geats for some fifty years and has led his people well. But a theft from the dragon’s lair (a barrow containing the hoard of a vanished civilization) arouses the monster, and Beowulf must face it. He intends to fight alone, as he did the Grendel-kin, but the dragon begins to get the better of him.

The weapon under consideration here is not wielded by the titular hero, but by Beowulf’s loyal retainer Wiglaf, who is unable to hold back upon seeing his lord suffer. At this moment, with Beowulf’s strength beginning to flag, both this new sword and its owner are introduced and discussed at some length:

Wiglaf wæs haten, Weoxstanes sunu,leoflic lindwiga, leod Scylfinga,mæg Ælfheres; geseah his mondryhtenunder heregriman hat þrowian.Gemunde ða ða are þe he him ær forgeaf,wicstede weligne Wægmundinga,folcrihta gehwylc, swa his fæder ahte;ne mihte ða forhabban, hond rond gefeng,geolwe linde, gomel swyrd geteah;þæt wæs mid eldum Eanmundes laf,suna Ohtheres; þam æt sæcce wearth,wræccan wineleasum Weohstan banameces ecgum, ond his magum ætbærbrunfagne helm, hringde byrnan,ealdsweord etonisc; þæt him Onela forgeaf,his gædelinges guðgewædu,fyrdsearo fuslic - no ymbe ða fæhðe spræc,þeah ðe he his broðor bearn abredwade.He frætwe geheold fela missera,bill ond byrnan, oð ðæt his byre mihteeorlscipe efnan swa his ærfæder;geaf him ða mid Geatum guðgewædaæghwæs unrim þa he of ealdre gewatfrod on forðweg. Þa wæs forma siðgeongan cempan þæt he guðe ræsmid his freodryhtne fremman sceolde.Ne gemealt him se modsefa, ne his mæges lafgewac æt wige; þæt se wyrm onfand,syððan hie togædre gegan hæfdon.-ll. 2602-30

His name was Wiglaf Weohstan’s sonworthy shield-thane Scylfings’ warriorAelfhere’s kinsman; his king he saw thereflames enduring under masked helm.In mind he recalled the kindness given:the Waegmundings’ wealthy homeland,every folk-right his father relied on.He showed little caution seized his shield-gripyellow linden-wood and ancient swordknown of old as Eanmund’s heirloomOhtere’s offspring. In open battleWeohstan slew that sorry outcastat that cruel edge-meeting, to his kinsman broughtthe burnished helmet ring-mail armorand ancient troll-blade. Onela gave him -his nephew’s bane - the battle-garments,finest war-gear. No feud would comethough his brother’s son had fallen, slain.Weohstan kept them many winters,sword and armor, until his soncould win, as he had, words of war-praise.Among the Geats then arms uncountedWiglaf inherited from his father’s hoardwhen the old man passed. Opportunity came nowfor the young fighter to further in battleaid his dear lord in the onslaught.His spirit stiffened like his sword-gift:battle-worthy as the worm discoveredwhen they clashed in combat together.

The history of this sword is complicated, but traceable. Wiglaf’s father, Weohstan, had slain Eanmund and taken Eanmund’s sword as a prize. Eanmund’s father, Ohthere, is a son of Ongentheow, the formidable Swedish king we will see in the following section, himself felled by a different ealdsweord eotonisc. Did Eanmund’s etonisc sword once belong to Ongentheow? A link between this weapon and Ongentheow’s past would seem fitting: it would make sense, given his apparent power, if he once had benefitted from eotonisc aggression. He may, then, have wielded Wiglaf’s sword in his youth.

There may also be a future for this weapon. Adrien Bonjour, in The Digressions of Beowulf, “proposes that [Wiglaf’s] sword might later have served a similarly pivotal role in the Swedish wars as the sword that Beowulf predicts will reignite the feud between the Danes and Heathobards (2032-56)”.2 If that were the case, it would be yet a further association of this eotonisc weapon with violent reversal of fortune: the young retainer of Ingeld slaying his father’s Danish killer and upending the peace of the wedding celebration.

After a speech in which he recalls Beowulf’s generosity and his fellow retainers’ oaths, Wiglaf rushes in to support his king. Beowulf, encouraged, strikes a blow against the dragon which shatters his (non-eotonisc) sword Naegling. The dragon retaliates, wounding Beowulf. The battle is going ill, but at this crucial moment Wiglaf’s blade bites. His eotonisc sword deals the blow that allows Beowulf to draw his seax and kill the dragon:

Đa ic æt þearfe gefrægn þeodcyningesandlongne eorl ellen cyðan,cræft ond cenðu, swa him gecynde wæs.Ne hedde he þæs heafolan, ac sio hand gebarnmodiges mannes þær he his mæges healp,þæt he þone niðgæst nioðor hwene sloh,secg on searwum, þæt ðæt fyr ongonsweðrian syððan. Þa gen sylf cyninggeweold his gewitte, wællseaxe gebrædbiter ond beaduscearp, þæt he on byrnan wæg,forwrat Wedra helm wyrm on middan.Feond gefyldan - ferh ellen wræc –ond hi hyne þa begen abroten hæfdon,sibæðelingas; swylc sceolde secg wesan,þegn æt ðarfe!-ll. 2694-2709

Then I have heard in the king’s hardshiphis upright earl true ability showedprowess and worth as was his wont.He gave no heed to the head, though his hand was burned -a man of courage, his kinsman aiding -but that demon of malice he struck lower down,the well-armed warrior, so the welling flamesbegan to ebb. Beowulf stillgoverned himself, gripped the war-knifethat hung at his belt, bitter and ready:cut the worm through the middle, the Ward of the Weather-Geats.The enemy they killed – courage ended his life –the dragon the kinsmen destroyed together,shoulder to shoulder; so should a man be,a thegn at need!

Again, as with the lair-sword, we see this ealdsweord eotonisc emerge, in the middle of a hard fight against a formidable enemy, in the hands of a young warrior, to turn the tide of battle.

And also, as with the lair-sword, here the eotonisc and the entisc are not far apart. Immediately following his victory over the dragon, the wounded and dying king beholds, as if for the first time, the construction of the dragon’s lair.

Đa sio wund ongon,þe him se eorðdraca ær geworhte,swelan ond swellan; he þæt sona onfand,þæt him on breostum bealoniðe weollattor on innan. Đa se ætheling giong,þæt he bi wealle wishycgendegesæt on sesse; seah on enta geweorc,hu ða stanbogan stapulum fæsteece eorðreced innan healde.-ll. 2711-19

It began then - earth-drake’s wound-workburning, swelling breastward pulsingsoon he felt it a hateful fire –poison spreading. A seat he foundbeside the wall the noble wonderingwisdom seeking - saw the ent-workhow stone arches upright pillarsenduring braced it - the barrow-building.

In this, his final battle, Beowulf is an old man. The entisc architecture comes at the end of the action; it is associated with the end of his life (and that of the dragon). And like Hrothgar before him gazing at the lair-sword’s hilt, Beowulf has nothing to say about the entish spectacle. His subsequent speech to Wiglaf is of the past that he knows, not of the barely-sensed glories of ancientry. For his own part, Wiglaf gives little thought to the past lives associated with the barrow or the treasures within, except that their absence has left the items in disrepair:

Đa ic snude gefrægn sunu Wihstanesæfter wordcwydum wundum dryhtnehyran heaðosiocum, hringnet beran,brogdne beadusercean under beorges hrof.geseah ða sigehreðig, þa he hit sesse geong,magoþegn modig maððumsigla fealo,gold glintinian grunde getenge,wundur on wealle, ond þæs wyrmes denn,ealdes uhtflogan, orcas stondan,fyrnmanna fatu, feormendlease,hyrstum behrorene; þær wæs helm monigeald ond omig, earmbeaga felasearwum gesæled. Sinc eaðe mæg,gold on grunde, gumcynnes gehwoneoferhigian, hyde se ðe wylle.Swylce he siomian geseah segn eall gyldenheah ofer horde, hondwundra mæst,gelocan leoðocræftum; of ðam leoma stod,þæt he þone grundwong ongitan meahte,wrætte giondwlitan. Næs ðæs wyrmes þæronsyn ænig, ac hyne ecg fornam.Đa ic on hlæwe gefrægn hord reafian,eald enta geweorc anne mannan,him on bearm hladon bunan ond discassylfas dome; segn eac genom,beacna beorhtost. Bill ær gescod-ecg wæs iren- ealdhlafordesÞam ðara maðma mundbora wæslonge hwile, ligegesan wæghatne for horde, hioroweallendemiddelnihtum, oð þæt he morðre swealt.Ar wæs on ofoste, eftsiðes georn,frætwum gefyrðred; hyne fyrwet bræc,hwæðer collenferð cwicne gemettein ðam wongstede Wedra þeodenellensiocne, þær he hine ær forlet.He ða mid þam maðmum mærne þeoden,dryhten sinne driorigne fandealdres æt ende; he hine eft ongonwæteres weorpan, oð þæt wordes ordbreosthord þurhbræc.-ll. 2751-92

I heard that soon the son of Weohstanafter speech-words from his wounded lord-kingobeyed the battle-sick, bore his ring-mailbraided war-shirt under barrow.Saw triumphant turning past him,brave retainer, treasures – jewels,gold on the ground glinting, scattered,a wonder on the wall, and the wyrm’s den -old night-flyer - vessels, pitchersof the old-ones none to own themlacking ornament; many a war-helmand old, rust-eaten arm-rings, braceletsartfully twisted. Too easily treasures,gold in the ground, pass through the gripof the one who hides them - whatever he tries.He saw, high above, a banner, gilded,over the hoard hanging wondrouslinked with hand-skill - light shone off itso that he could see the hoard-hall’s floorand the works of cunning. The wyrm had left therenot one sign - the edge destroyed him.Then I heard the hoard was plundered,work of the old ones, by one man only,piled in his arms the platters and gobletshis choice of treasures; the standard also,brightest beacon. Blade had ended -edge of iron - the old ownerhe who had warded the wondrous treasuresfor an age on earth, waging flame-warbefore the barrow burning firesfierce at midnight ’til death unmade him.Wiglaf hastened - for his war-lord eager -treasure-laden; troubles gnawed him –would he meet alive in lively spiritson that death-ground Geat-king Beowulfwaiting strength-drained where he’d left him?He bore to his folk-lord the finest treasuresfound him bloodied famous leaderlife’s end approaching. Again and againhe sprinkled water ’til speech-words startedburst from breast-hoard.

To sum up, then: here (as with the third eotonisc sword, which we will examine next week) the eotonisc and the entisc follow each other relatively closely (the eotonisc sword appearing in l. 2616, and enta geweorc just over a hundred lines later, in 2717 and 2775 ) and yet are associated with their respective spheres: heroic action, victory at a crucial moment on the one hand; and the end of life, contemplation of the past, on the other.

Some take the “enta geweorc” of l. 2774 to refer to the hoard’s treasures. The editors of Klaeber 4 think it “most likely” that this phrase refers to the “stone chamber rather than the hoard itself” (p. 256). Either way, the ent-work in this passage is associated with the death of its owner, the dragon; the treasures appear decayed, and are soon to pass (briefly) into the possession of a dying king. Whether the ent-work is to be taken as the rich but partially ruined metalwork, or the stone architecture of the barrow, its use and associations here are consistent with the other appearances of enta geweorc in Old English literature.

Now that we have seen two of the three eotonisc swords, we have some perspective from which to evaluate one theory about what these eotenas meant to the poet.

Some commentators and translators see the word eotonisc in the phrase ealdsweorc eotonisc as “merely indicative of great size”.3 Thus for example Francis Leneghan translates “ealdsweord etonisc” (2616) as “the gigantic ancient sword”.4

But only one of these three swords - the sword found by Beowulf in Grendel’s lair - is certainly huge. There, the poet makes a point of stating that no other man could have wielded it. As for the other two swords, their wielders Wiglaf (as we have seen in this post) and Eofor (forthcoming) are not said to be stronger than average, and the weapons themselves are not said to be oversized. To describe all eotonisc swords as “gigantic” would seem therefore to be unfounded, conditioned perhaps by the evidence of the lair-sword, assumptions about the physical stature of eotenas, or expectations from Old Norse contexts making use of the cognate jotun.

Furthermore, if eotonisc always meant “huge”, we would expect the word to more frequently correlate with huge things. Most entish objects are evidently large stone structures, and yet the adjective “eotonisc” never describes such works when they appear in any Old English texts, whether The Ruin, The Wanderer, Beowulf, or Andreas. Eotonisc therefore seems not to mean “over-large”, but “eoten-ish”, that is, “associated with or made by eotenas”.

Next week, we will end this series with Part III and an examination of an episode in Beowulf that offers a final test for the meanings of eotenisc and entisc works.

Old English text from Klaeber’s Beowulf, 4th edition. Translation mine.

Quoted in The Dynastic Drama of Beowulf, Francis Leneghan, pg. 190.

Clemoes, Peter, Interactions of Thought and Language in Old English Poetry, pg. 28.

Leneghan, Dynastic Drama, pg. 96.